Iteration Beats Stagnation, Momentum as a Better Beacon Than "Progress"

What innovation leaders and teams can do when clarity is scarce, timelines are fuzzy, and forward motion is hard to come by.

This post is part of a recurring series focused on Execution In the Arena: Project Leadership and Tactical Applications — the second pillar of the From Here to There game plan. How do you actually work with your people to move forward? Here, we discuss tactics, strategy, and specific aspects of the operational and functional core of reaching your destination.

My longtime mentor and Director of Orthogonal Research and Education Laboratory, Dr. Bradly Alicea, would often make a distinct remark to us in various project meetings, particularly when someone was stuck or perhaps felt uneasy about the lack of visible outputs. Momentum can be more important - or perhaps a better target, beacon, or barometer - than [visible] progress. Or put another way, iteration beats stagnation. Of course, the nature of your organization, project, deadlines, and what you have to answer to for success to be realized, will condition how this principle is applied.

Ahead, we will discuss how this principle can be used as a lens to comprehend situations, both as a manager and as a member of a team.

1. Background: The Problem Space of Arriving at a Destination

There is a fundamental tension between people’s time, attention, and ability to pursue a goal or strive for something that does not yet exist. This is an imperative and often under-emphasized aspect of all manner of innovation, research, exploration, or situations wherein what you are trying to achieve is not a matter of duplicating or reproducing something else. There is a complexity at hand, and to maintain the focus of the destination when the path to it is unclear, requires skills, literacy, and ability to communicate. The role of a “leader” or manager in this capacity, formal or otherwise, is almost as an ambassador, between the Destination and the Project Team. Diplomacy is at hand, for how the Team can create, produce, or otherwise “travel” towards the Destination, outcome, or deliverable. What’s more, the “Destination” may not be exactly where its location was determined at the very outset of the endeavor.

In essence, the role here of the manager is to not let the Destination seem too far away while indicating what incremental steps to take. Or, how to identify what steps can reasonably be endeavored for, and are worthwhile stepping on, in order to either reach the Destination, or perhaps a safe and tenable waypoint.

2. The Challenge: Everything looks perfect from far away

One of the primary challenges in this space is that a high quality final product may seem both inspiring and daunting. Even, a “minimum viable product” (MVP) itself may seem like settling, or simply not as interesting, or in lesser cases, potentially even a distraction or a bridge to nowhere.

In innovation work, it’s often not the most brilliant idea that wins — it’s the team that keeps moving.

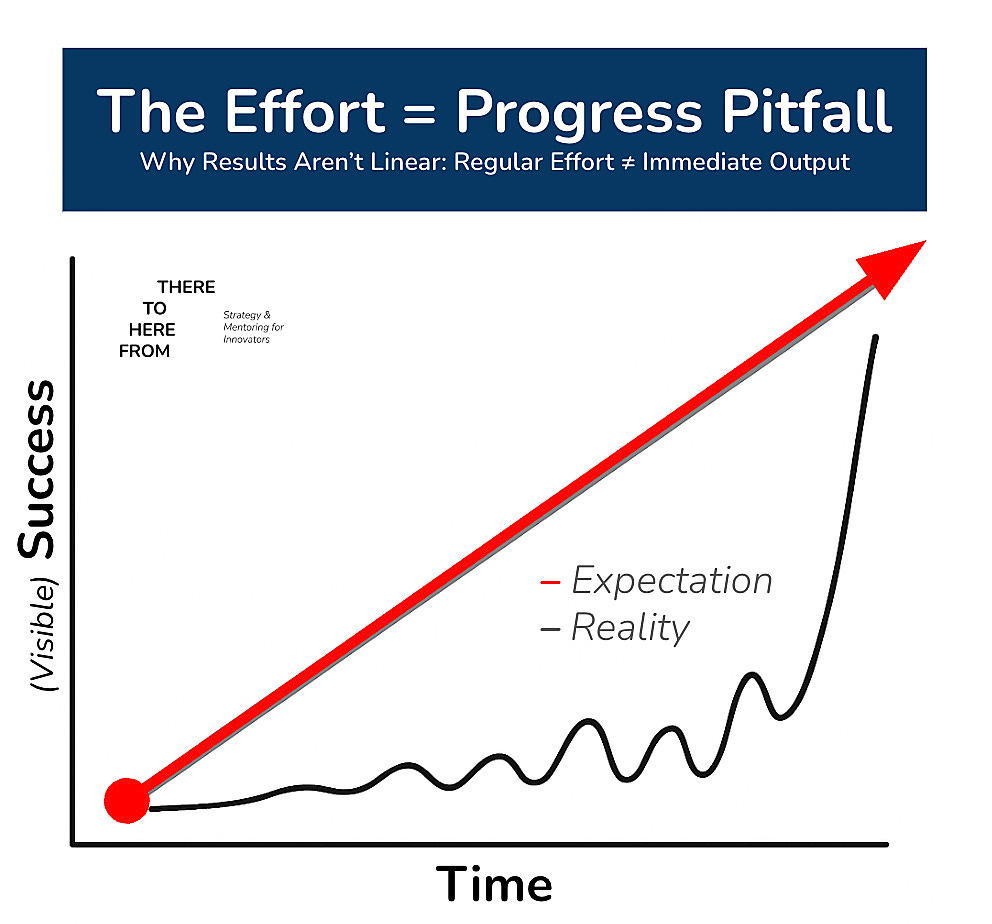

Core idea: what looks like "progress" from afar can actually mask inertia, while smaller, imperfect steps forward build momentum and clarity.

A less pithy and more real phrasing would be: In innovation work, it’s often not the most brilliant idea that wins — it’s the team that keeps moving… or at least, keeps moving enough without painting itself into a corner or depleting its resources (including motivation).

So now the dilemma takes more shape:

From a leadership perspective, you want people to be engaged, moving towards a target, and able to receive reward or positive feedback about their efforts.

From a teammate standpoint, the goal is to keep showing up and finding ways to have faith, particularly the more you have to innovate or generate something new.

3. False Gods: Chasing “Progress” as a Fixed Ideal

Many teams (perhaps especially early-career or academically trained) conflate progress with polish. This is to say, what you make should look good, or very good, and each step must Look Well-Polished before the future can be realized. What determines how much this is the case are a myriad of factors, including the domain, industry, deadlines, funding constraints, and so on. But for the purpose of this discussion, we’ll speak generally about when and where polish is appropriate.

In more collaborative teams - or simply a group of co-founders sorting things out - one of the biggest bottlenecks is the disparity between how things looked within everyone’s individual head’s vs what the singular artifact being made actually does, or how it looks. You may turn to things like Convergent Facilitation to attempt to sort this out, but part of the Ambassadorial work of the Project Lead is to find tenable iterations to pursue. Idealism or perfectionism often slows things down — delaying launches, over-scoping, or causing fear of iteration.

Normalizing the disparity between Exciting Glorious Complete Vision and the more tenable steps is key. Many times founders or leaders will put immense pressure on themselves to “make something perfect enough” that other people can build on, without finding these intermediary steps. Or, you may be working in a situation where a C-suite individual only wants to hear about how close to that Exciting Glorious Complete outcome you are, and any other updates are Bad News or Demotion Worthy. These are all factors that get in the way of actual communication about what is happening, and can disrupt the actual flow of iteration & maintaining momentum.

Beware “performative” progress: updates, roadmaps, docs that look great but don’t move anything forward.

Furthermore, when innovators are in a culture that puts misguided expectations on them, there may be even more pressure to produce “performative” progress to appease those pressures or pressure perpetrators. This, too, is an even further distraction and resource-waster, sapping precious focus, momentum, and potentially even commitment.

Aside: There is another consideration for another time, which is, how much is “Project Management” itself (or at least some of its documentation & visualization, perhaps) performative or a waste of time - stay tuned for that.

It is imperative that leadership maintains the means for actual iteration and momentum to flow; this is one of the most important top-down things that can be done, as without it, project leads have limited ability to make tactical recommendations or support their team in reliable ways. “What to do when C-Suite isn’t giving you what you need to support your team” will assuredly come up in future discussions, as well.

4. The Power of Iteration: Prototypes, Process, and Learning Through Doing

…or releasing, or “Demo-ing”, or drafting, or versioning, or otherwise segmenting and allowing for revision and feedback.

If The Top of the organization is giving teams and leaders space to flourish, here is a classic set of advice on what and how to proceed. We’ve come this far without using terms like Agile or Scrum Master, Waterfall, or similar, and for this piece I will leave them aside in favor of somewhat more concrete or tactical examples and applications.

Rapid iterations — even when messy — create momentum, shared clarity, and adaptive insight.

My personal favorite variant of this may be using a whiteboard (yes, physically), or a digital variant. There is something deep-seated within us that seems to correctly attune or have innate context for badly drawn diagrams and the humility of attempting to co-discover or co-interpret what message is trying to be sent and whether or not it is communicated well-enough. Indeed, there are cognitive scientists, such as Dr. Judy Fan of UC San Diego and now Stanford, focused on topics like drawing as a cognitive tool. But I acknowledge this may be my personal preference.

Nevertheless, some form of everyone staring at the same blank space, and making landmarks of what needs to happen relative to what is going on right now, is a great way to break through clutter, distraction, and siloed headspaces. The simple act of making an actual “conceptual iteration” or “this week/sprint’s map” might be of use.

Beyond that, iterations of MVPs can be of use, but also iterate on the components: what is an outline of this post or documentation; what are the key features we’re working around for this part of the development process? By trying to “complete” the actual step or stage the team is at, it can ideally identify the decisions that need to be made. Iteration can, at best, be used to move from states of unknown to states of paused-do-to-choice/decision-selection. Some decisions cannot be made by the people who discovered they require a selection of options.

So, again, get your map of the parts, ideally from start to finish, as loosely and roughly as they seem to still be of substance, and then minimally build out what you can, connecting the stages or tasks. Emphasis turning up and identifying what decisions need to be made, or, how findings fit with expected functioning, or expected conclusions. Normalizing “failure” perhaps isn’t the approach, and yes “fail forward” might fit here, but the goal is more so to actually legitimize the esteemed “bias for action” that we all want to have. Reward folks taking action, and empower them to be wrong, or that identification of options is important; this seems obvious, but I implore you to reflect on how critical it is for innovators - for folks who do not yet have a blueprint to reproduce.

Iteration as movement as affording momentum; polish as illusion as (potentially) arbitrary when the entire path forward has yet to be demarcated.

Tech startups, experimental science teams, or skunkworks projects often succeed (or “progress”) most through shipping and learning. This can be challenging especially the more proprietary or Stealth Mode you are operating within, but there are ways to emulate it, even if it is in-house. In one of my lab experiences, our weekly stand-ups were opportunities to do this. It did not always happen, but having the space and setting the expectation of “iterating” on what you had was vital. Tending to that environment, and going beyond “Demo or Die”, is another worthy discussion to have. But the general atmosphere can be of completing the circuit, so to say: a goal is established, an individual or group considers the path, they move on the path, and then the movement is relayed to the larger group, in order for the group to provide feedback.

The critical moment is the actual relaying to the larger group, as that is the inception of the actual iteration: the “building” process has to stop, at some point, in order to be conveyed to The Others. The common pitfall is that movement on the path is fragmented, and there are disparate headspaces or considerations about what is next, and the team is lost. It is a precious and immensely valuable thing, if you can establish a organizational culture where this is actually rewarded; the exploration, the stopping, the forming of communications about what happened, and the constructive feedback. It’s much easier said than enacted, and the quality of the iterative process can make all the difference in whether or not something actually happens, turns a profit, or comes into reality in any form at all.

A Comment on Increasing Your Organizational Literacy

Many founders or visionaries have difficulty with this space, as there is a legitimately challenging paradox to operate within, of identifying and demarcating the Exciting Glorious Complete Vision as “something they just have to do themselves.” The pressure can be crippling to “do more” or “refine more”, and there is a sense that one’s baby is being placed in the care of Others, and trust around that can be difficult to maintain. Or, on the other hand, a CEO or C-Suite wants to have something happen but is only so invested in it, or has tremendous experience in one area, but not enough in the other, so they are less concerned with due diligence for managing said paradox.

The influences and pressures shaping iteration are endless, but we as innovators can bring some theory, models, and language to better navigate them.

To this end, knowing where things stand can save you a lot of stress in terms of evaluating what to do given whatever position or role you are in - we hope this essay will help to increase your literacy and comprehension for doing so.

5. For Managers: How to Build Momentum Within a Team

For practical, direct advice:

Lower the stakes for small wins — create cultural permission for "drafts" or experiments

Shift timelines from “launches” to “releases.”

Reward learning velocity over idea purity.

Encourage documented iteration — think versioning, changelogs, reflection memos.

Structure weekly work around "what’s the next thing we can try, test, or publish?"

Particularly, the last point stands out to me as what is overlooked quite frequently. As noted above, the goal in many ways is to discover the decisions that need to be made. The goal for the Ambassador / Manager in this case is get this information from the team or from those “in the trenches” doing the work and interfacing directly with the trouble, and pushing for alignment, consent, and confirmation of direction from the Top (from the highest level decision makers).

The biggest unknown unknown in many ways for innovative processes are what are the decisions we will need to make that are not clear at the outset, and how hard are they, how long will it take to decide, and what other insight, information, or expertise should we get to help us with them? More so than “doing or building” directly, those decisions will matter.

So, what else can you do, as a manager?

In the Main Quest line of identifying critical decision spaces, it may be useful to vary the focus of what the team or individual members are focusing on. It is theoretically wise to only focus on high impact high effort projects most of the time; yes, it is a rational use of effort when aiming to push bigger things forward. But there are times when perspectives need to shift, or as noted at the very start of this essay, the attention, effort, and buy-in from the team will need to be cared for.

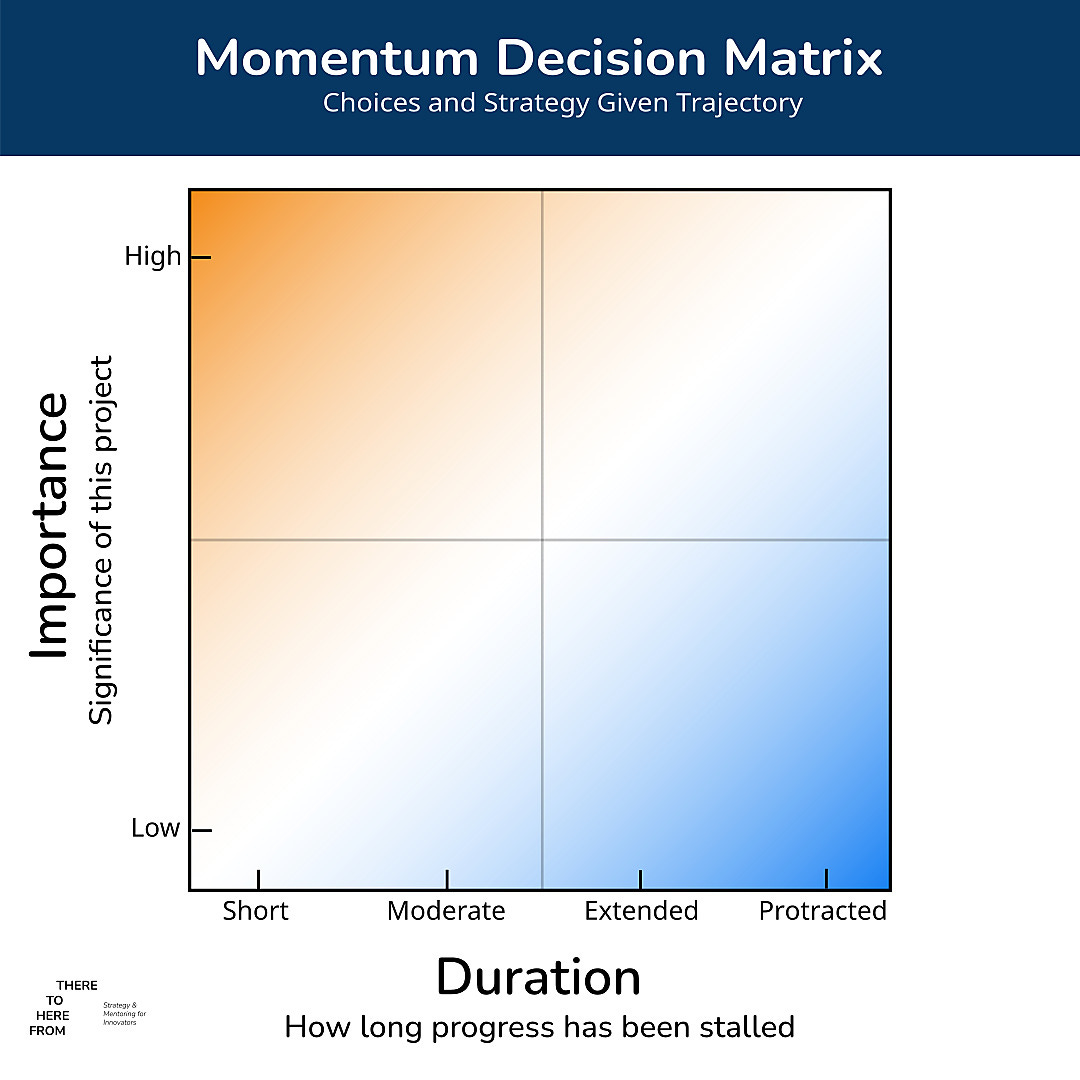

It would be folly to advise a group takes up busy work. But the above diagram may offer some context for different sorts of things to “do.” Are there quick, easy wins within a given project? Are there low-effort, fill-in tasks that might simply need to just get done in order to free up someone’s time, or unlock something unforeseen? Avoiding the thankless task / money pit type situations is wise for not damaging morale or buy-in.

Beware, giving folks work that is not project relevant when you are still waiting on decisions to be made - particularly from the Top - is a recipe for further stalling out. In an ideal situation, you may perhaps be able to rotate foci, or do another, meaningful important project in the meantime. But depending on your funding, demands, or deadlines, you may have limited variability there.

There is a particular art to directing focus of the team properly; the contexts for the challenges affects how hard this is to do, and whether or not the manager is experienced in doing so, or familiar with the problem spaces at hand. Once again, there is a delicate balance between having people’s time be used well and relevantly, and moving a project forward with many moving parts of varying degrees of complexity and decision ambiguity.

For now, let us turn to what teammates or “non-managers” can do within these contexts, before we reach our conclusion.

6. Teammates: How to “show up” and maintain momentum when it’s unclear what to do

If you are on a team where you feel momentum fading, and iterations harder to come by, what can you do?

For the sake of brevity, I will say as a manager you ideally will be able to see this before it happens, or at least plan for it - or even be able to designate secondary and tertiary goals or targets for your team.

As a member of a team, waiting for others to make decisions is one thing. Being unclear how to proceed (particularly in deeper research spaces), is another. In essence, showing up matters, and talking about what you are seeing and doing matters. Articulating it and communicating it to another matters, but particularly to people who aren’t observing you every day; their opinions and perspectives can guide the focus of your proceeding attention. You have some agency in the iteration process, and it is wise to wield it.

But what about other factors? How do you show up in the face of vast uncertainty, or develop an intuition of what you should be working on?

In an upcoming article, we’ll discuss this diagram more fully and identify what to do at various positions in it, with an emphasis on what a teammate should be doing therein. This a critical skillset for innovators to develop - and if not a skillset outright, an intuition, accrued experience, and general sense of what options are available, when navigating such murky spaces. What’s more, there’s a decent chance your manager may only be so skilled, familiar, or artful themselves - so it may be on you to sort out how to “manage upwards”, as the saying goes.

6. Closing: Momentum as Strategic Culture

It’s worth considering how success is defined at large, and in particular, how you in your role - C-suite, manager, or team member - are evaluating yourself and others in accordance with it.

In particular, how is “progress” discussed or modeled in your organization? Is progress referred to begrudgingly as distance to a fixed goal? Is it a supportive, iterative environment where the management is comfortable addressing road blocks, lulls, and has constructive and insightful mitigation practices? It’s likely somewhere in between. But there is something to seeing how things could be different, or, appreciating the effort others have put into enabling better practices, too.

The argument here is for momentum as a culture of engagement, feedback, and movement, rather than aiming to be "right" or "ready."

In general, remember that when you are particularly stuck, sometimes movement in and of itself is the answer: You can’t steer a parked car. Movement isn’t just better than stagnation — it’s often the only way to know what direction to take. Present the best of what you have to someone else, and see where it leads you.

For C-Suite and the Top of the organization, it’s worth considering how your decisions, expectation management, and communication styles influence the all-important momentum of your teams.

For the Leads and managers, consider the impact of maintaining momentum and the relative morale of the team you lead. This is all inherently tied to buy-in and trust of the vision you are aspiring towards - what you are asking others to believe in. As a lead, people are implicitly trusting you to navigate the effort period, and you are managing your “leadership capital”; you’re saying if you go here, and channel effort in this way, good things will happen.

And for the actual team members - stay tuned for more on what to do during the different contexts you may find yourself in, as you attempt to ride waves of momentum, iteration, and hopefully, valuable outcomes and progress.

Do you have any experiences, advice, or suggestions that stand out to you, regarding sustaining momentum - or the pitfalls that prevent such? We’ll be doing some interviews around this topic soon, so please reach out if you’re interested in a discussion.

Special thanks to for graphic design support on Figure 4, and for editorial and advisory input on visual direction for Figures 1-2.

This post is part of our series Execution In the Arena: Project Leadership and Tactical Applications, a recurring series focused on project leadership and tactical decision-making for research and innovation teams. This series is the second pillar of our Game Plan, aimed at team leads, project managers, and operational builders looking to navigate ambiguity, keep teams aligned, and turn momentum into meaningful outcomes.